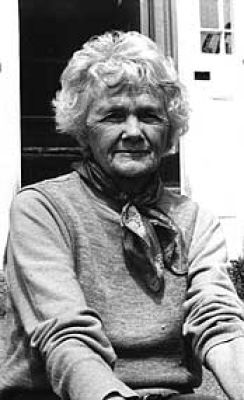

The following is an interview with Daphne du Maurier at her home Kilmarth, where she was to spend the last years of her life. This house is described in her book, The House on the Strand. The interview took place in 1977 when I was 5 years old.

Photographs and article - Chris Simons

LADY OF KILMARTH

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spokes of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited.

There are few readers who will not recognise that paragraph as the opening of Daphne du Maurier’s most famous novel, Rebecca. This haunting tale of true Gothic suspense has remained a best seller for over fifty years. Perhaps there was a little precognition in those lines, or it may have been merely a memory of the author’s discovery of the house on which she based Manderley.

We came to the lodge at Four Turnings, as we had been instructed, and opened the creaking iron gates with the bluff and false courage common to the trespasser. The lodge was deserted. No one peered at us from the windows.

Thus Daphne describes her first attempt to find Menabilly. Later she sees the house and her feeling for the place is very apparent. Grey, still, silent. The windows were shuttered fast, white and barred. Ivy covered the grey walls and threw tendrils round the windows. It was early still, and the house was sleeping. But later, when the sun was high, there would come no wreath of smoke from the chimneys. The shutters would not be thrown back, nor the doors unfastened. No voices would sound within those darkened rooms. Menabilly would sleep on, like the sleeping beauty of the fairy tale, until someone should come to wake her.

Why was the house deserted? The question intrigued the young writer. This was the start of a love affair with a house and the inspiration of three of her most popular novels. This house became Daphne du Maurier’s home for over twenty years. Many of her happiest memories are contained within this place where her children grew up. But, when Rebecca was written, Menabilly was deserted and overgrown. When I visited Daphne, rumour had it that the old house was once again empty and neglected. Perhaps that was just another story, or perhaps the old ghosts had again taken over their former abode. Daphne du Maurier left Menabilly in 1967 and moved to another old house a few miles along the same lane.

To anyone who has read The House on the Strand, the name Kilmarth has a ring of magic. This was the house with an old basement once filled with embryos in jars and other strange objects. This was the house which had risen above the foundations of Roger Kylmerth’s fourteenth century dwelling. This was the house where I visited Cornwall’s best known and best loved writer.

I was welcomed to Kilmarth by the author, while my young son was taken to meet two puppies.

“I have always had West Highland terriers,” said my hostess. “My last one died some months ago, but I felt it was now time for some new ones.” As she spoke, she led me into a comfortable sitting room, which bore some evidence of her trade. There were photographs everywhere, mainly of the author’s family.

I felt instantly at home with this charming woman who had been one of my personal heroines for many years. We had corresponded previously about some local research in which I was involved, and she had shown a genuine interest in my work, giving me some useful advice. Naturally, the conversation soon turned to Daphne’s own work and I was able to ask a question that had haunted me for a long time.

“In My Cousin Rachel, was Rachel good or evil?”

Her tanned face creased into a smile beneath her silver hair. “Lots of people have asked that and, to tell the truth, I don’t know. You see, I was Philip when I wrote the book.” She went on to explain. “When one is writing a novel in the first person, one must be that person. What about the hero of The House on the Strand? What did it mean when he dropped the telephone at the end of the book? I don’t really know, but I rather think he was going to be paralysed for life. Don’t you?”

Many of her novels have finished with an unanswered question. In one case, this caused a rather annoying enquiry from a writer in America. Could he write a sequel to Frenchman’s Creek? Daphne telegraphed an immediate reply to say he most definitely could not. She strongly objected to other writers producing the sequels to the novels of living authors, and who can blame her? She felt almost as strongly about sequels to the work of dead authors, but sadly she had no say when it came to it.

Places have often been the inspiration for her books. Kilmarth and Menabilly are obvious examples and, in the former case, much of The House on the Strand is the actual history of the house and surrounding district. Jamaica Inn was a place where the author once stayed with a friend. After being lost on Bodmin Moor in the dark, her imagination was stimulated by the remote location of the inn an ideal hideout for smugglers and cut-throats! When she passed the inn in later life, Daphne felt a little twinge of guilt as the place had become quite a commercial enterprise, but on a dark Winter evening it still has a little of the atmosphere attributed to it in the novel. Today many of the furnishings of her own home are displayed in the Jamaica Inn Museum.

Frenchman’s Creek is an inlet on the Helford river where Mr and Mrs ‘Boy’ Browning spent their honeymoon. Perhaps this is why it was Daphne’s only romantic novel. The youngest major in the British Army sailed to Fowey in the Summer of 1931, just to meet the author of The Loving Spirit. But it took him until April the following year to effect that meeting. Apparently it was love at first sight and they were married three months later.

Perhaps Daphne was more fortunate than many young writers today. She was born into a well known family in the world of arts, and had more encouragement and opportunity than most to become a novelist. Her grandfather, George du Maurier, was the author of Trilby and a well known cartoonist for Punch. Her father was the equally well-known actor manager, Gerald du Maurier. The young Daphne mixed with many prominent writers of the day, including J.M.Barrie, whose lost boys were her cousins. She received a great deal of help from Sir Arthur Quiller Couch, the legendary ‘Q’, who was a neighbour in Fowey. But it was a place, rather than a person, which was mainly responsible for her ultimate success. Cornwall was the only place in which she could really write. Somehow the words did not flow in London, but the peace and beauty of the far West inspired all the books that took shape under the pen of Daphne du Maurier.

The Loving Spirit was Daphne’s first novel, a saga about a family of Cornish boat builders in Fowey. The book sold well and was the first in a long tradition of novels based in Cornwall. There have been stories set in other places and other countries, but the Cornish ones seem to have been those with the greatest impact. Not only novels, but also many strange short stories such as The Birds are based in Cornwall, although others, equally famous, for example Don’t Look Now, take place elsewhere.

She knew that it was this peace that she had wanted when she came away from London, and had come to Navron to find... through the woods, and the sky, and the river. This an excerpt from Frenchman’s Creek which might be Daphne voicing her own feelings, and there are many such passages in her novels, expressing the fascination and love for Cornwall which has attracted so many writers and artists to this corner of Britain.

Our talk of places and old houses led to a conversation about atmospheres, and we discovered a shared belief in the impressions left by previous inhabitants. But what about ghosts?

“I believe some people are susceptible to that type of thing. Fortunately, I’m not.” She smiled and went on to talk about how one can find out about these people who lived so long ago, leaving some echo of themselves in the old stone walls. “I was lucky. I found an old man who knew a lot about local history. He was extremely helpful.” She told me where to find more information about the past of my own home. “Local and county libraries, County Records Offices, Parish Registers. You find out as much as you can, then build your story around it. For example, I know Roger Kylmerth lived at Kilmarth in the fourteenth century. Nut I don’t know what he was really like. He may have been entirely different to my Roger!”

Daphne had always been an avid reader, and among the novelists she admired were the Brontë sisters. She had visited Haworth, the home of that talented family, when she was researching her biography of Branwell, the tragic brother of the famous trio. She had recently discovered that the Brontës themselves used local history in their books, and told me she had a contact in Brontë country who was researching a local family who may have proved to have figured prominently in Wuthering Heights. It is certainly interesting that Emily Brontë may have been clothing fact with fiction in the nineteenth century in the same way that Daphne du Maurier did more recently. Even Daphne’s interest in the Brontës had a Cornish connection, as Mrs Brontë was originally Miss Branwell of Penzance.

Growing Pains, Daphne's autobiography was published in 1977 to coincide with the author’s seventieth birthday. It is the story of the shaping of a writer, and paints a vivid picture of this writer’s childhood. The book ends after the publication of her first novel and her marriage to Major Browning. This must have been a very romantic occasion. When the couple sailed off down the river on their honeymoon, the inhabitants of Fowey turned out in force to wave them off. The Cornish people had obviously taken the young writer to their hearts. As she had taken Cornwall to hers.

What makes a writer? I feel that writers are born, or at least the compulsion to write is born, and I’m sure Daphne would have agreed with me. Naturally, environment helps, and so does the availability of reading matter. Few writers have exposed the development of this talent in the way Daphne did in Growing Pains. We see the child reading her way through a varied assortment of authors, and we see her creating little fantasies, which she and her sisters act out. We see her early attempts at poetry and stories, right up to the time when she writes her first novel in eight weeks at the age of twenty one. Not only this, but an independent and sometimes unconventional personality emerges.

Imagine a young, rather innocent girl in the nineteen twenties, who is receiving amorous overtures from an elderly millionaire. It is a lovely Summer day and they are sitting beside a Norwegian fjord. How does the young writer escape? She strips completely and dives into the water! Rather alarmed, her potential suitor offers her a fur coat, perhaps to hush the whole thing up. Daphne refuses and expresses her preference for a dagger. Not exactly what one would expect from a well brought up young lady of that era, but effective nevertheless.

When I asked Daphne if she planned a sequel to Growing Pains she replied, “No. I believe one can become too introspective writing this type of thing. I intend to look to the future rather than the past.” She denied that there was anything more of interest to write about herself. “All I can say is that I had a very happy married life and have a delightful family.” She paused. “And I don’t like books which are full of name dropping.”

Perhaps there was no need for a further work on this subject. After all, a writer’s work is almost always partially autobiographical, and I feel Daphne expressed many aspects of her life and personality through her varied writings.

One thing Daphne always had was a sense of fun. On one occasion, she was slightly annoyed to read some comments by Antonia Fraser in a newspaper. The gist of these comments was that everyone had misunderstood the novel Rebecca. In Ms Fraser’s opinion, Rebecca was really good whereas Max was a rotter and his second wife was no good either. The misinterpreted novelist decided to get her own back, and the way to do this seemed to be through Ms Fraser’s new biography of Cromwell. A short feature consequently appeared in the same newspaper stating that Daphne du Maurier had discovered some hitherto unpublished documents which proved conclusively that Charles I and Cromwell had enjoyed a homosexual relationship! The end result was an exchange of friendly letters between the two authors, each now appreciating the other’s joke.

“Have you read Antonia’s novel, Quiet as a Nun?” Daphne asked. When I shook my head, she continued. “Read it, and let me know what you think. I think she ought to stick to writing biographies.”

When I visited Daphne, writing was still her main compulsion, but she had other occupations too. Her family was very important to her, and so were her dogs. She loved walking and gardening and dressed very casually to enjoy these pursuits. So what was next on her agenda? Well, her home, Kilmarth, had not yet revealed all its past, and the Bakers who lived there in Tudor times may have had a story to tell. Research was underway once more, and Daphne seemed to derive as much pleasure from that as from the actual writing of the novel. The discovery of the facts, particularly about the place where she lived, was always an exciting occupation.

Sadly, that novel never materialised. I believe the last thing to have been published by Daphne du Maurier was a small book of memories, The Rebecca Notebook. That was in 1981. She continued to live at Kilmarth until she died, but I believe I was one of the last persons to interview her.

In the meantime, bookshops everywhere display the many works of Daphne du Maurier. Short stories, biographies, travel books and novels cater for varying demands of readers all over the world. Even those who do not read have seen or heard of such films as The Birds, Rebecca, Don’t Look Now and many more. Humour as in Rule Britannia, tragedy as in My Cousin Rachel, romance as in Frenchman’s Creek, family sagas as in Hungry Hill and The Loving Spirit, and Gothic novels such as Rebecca have all been produced by the versatile writer who continues to be one of Britain’s best selling novelists.

My time at Kilmarth drew to an end, and Daphne took me outside to where my son was playing on a swing, suspended from a large tree. She posed smilingly for some photographs in the garden and on the steps outside her house, then shook my hand and wished me success in my own writing.

As I drove away, one though was uppermost in my mind. This charming woman, whose name was known throughout the world, had cared about me for a short time. With unfeigned modesty, she had shared an hour of her precious time with a stranger, an unknown writer. One final touch arrived several days later a lovely postcard of Kilmarth inscribed with Daphne’s best wishes. Daphne du Maurier is still one of my heroines.